What is ‘Doughnut Economics’ and Why Should We Care?

Traditionally, a fast-growing GDP is the key to a healthy and successful economy. Many economic models focus on how to maintain and generate increases in production. Intuitively, more is preferred to less, so why shouldn’t growth be the objective?

However, many economic growth models fail because they assume unlimited growth is achievable. Indeed, the 2008 financial crisis was a consequence of the long-held belief that a constantly growing economy is always desirable and feasible.

‘Doughnut economics’ rejects this idea in favor of a circular or regenerative system. This new model was created by self-described ‘renegade’ economist Kate Raworth in 2012 as a counter to growth-based policies. It is an important theory to consider since it moves away from antiquated economic reasoning and provides the necessary thinking to address 21st-century concerns. Doughnut economics creates a space within the field to reasonably discuss environmental and social issues.

Source: TIME

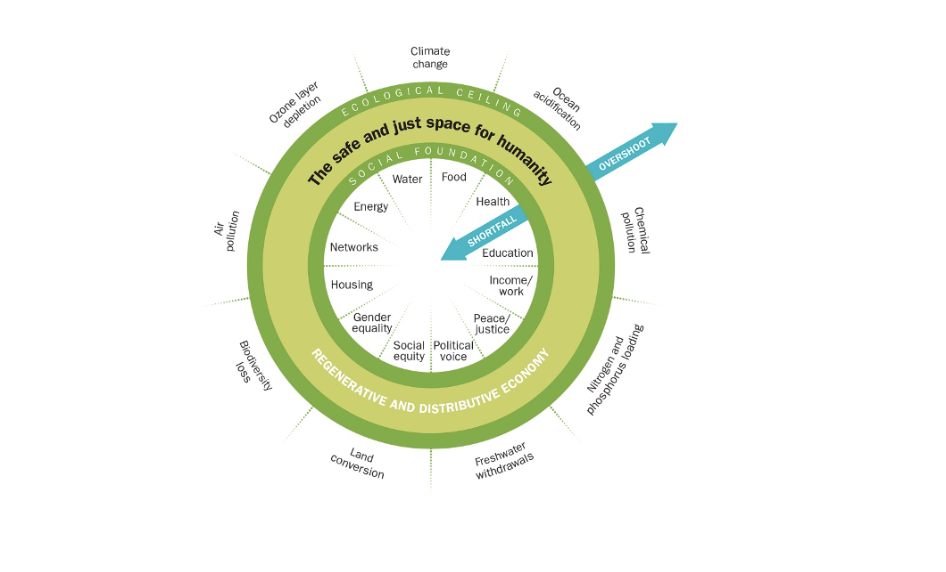

Raworth’s doughnut-shaped diagram is meant to be a visual representation of the safe space for humanity to exist in. Our goal should be to remain above the “social foundation”, the inner crust of the doughnut, but under the “ecological ceiling”, the outermost layer. Whenever a society falls into the doughnut hole, it has failed to meet the basic needs of its citizens such as proper nutrition, education, social rights, etc. The outer boundary represents a case in which environmental boundaries are violated, such as climate change problems, pollution, and biodiversity loss. Raworth’s doughnut effectively demonstrates the possibility of a circular economy. A system that prioritizes the reuse of resources and goods to sustainably extend their production lifecycle. This type of economy is less destructive than a system centered around constant production growth.

It's just another model, why is this one any different?

Raworth’s work is significant because it presents a new outlook within the field of economics that can tackle modern challenges such as social inequality and environmental degradation. Strongly aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, her theory offers a revision of the goals of our economic system by urging communities to build strong social foundations while also being conscious of our planetary limits. It is certain that her model is more people-oriented than typical economic theories that reduce all individuals to one representative consumer. Furthermore, Raworth opens the floor in the world of economics to talk about the limits of our planet’s resources and environmental sustainability. Of course, the economic assumption that more is always preferred to less must take into consideration a finite pool of natural resources. On the podcast Freakonomics hosted by Stephen J. Dubner, Raworth explains that “there was just no option to study anything environmentally ” aside from externalities when she pursued her economics degree. The circular model manages to give environmental issues a bigger space in macroeconomic theory. By reframing economics, Raworth’s theory will be a great instrument for governments, policymakers, companies, and individuals to gain a more holistic understanding of economic development.

Raworth’s work is also special in that it goes beyond simply existing theoretically. It is currently being applied in the real world!

Amsterdam is the first city to embrace the new theory. The city made the decision to implement doughnut economics in the early stages of the COVID-19 lockdown to alleviate some of the financial stress imposed by the pandemic. It wanted to make sure the city could be more resilient to future shocks as well. Certainly, a healthy economic structure should not immediately break down in the face of unexpected situations. This would be mitigated by a circular system, which ensures everyone has access to basic needs. Amsterdam plans to increase its recyclability and lower levels of resource extraction with the intention of becoming fully circular by the year 2050. The Dutch capital uses a circular approach to its housing policy. When creating new developments, 40% needs to be affordable housing, 40% must be middle-income and the remainder is left to the free market. Naturally, these new developments must also be practical. Instead of demolishing and rebuilding existing edifices, Amsterdam asks building companies to work with what is already constructed and adapt the structure to fit a new purpose when necessary.

Amsterdam is not alone in applying Raworth’s work. Copenhagen (Denmark), Brussels (Belgium), Dunedin (New Zealand) and Nanaimo (Canada) have all begun the transition to a circular economy.

Slowly moving away from growth-based policies will avoid vulnerability to situations like the 2008 recession or the pandemic’s financial crisis. Raworth’s doughnut economics might just be the blueprint for a more sustainable society.

Edited by Vighnesh Avadhanam & William Daunais

Featured Image "Doughnut / 冬甩" by 娜娜. is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.